Although the case had its complications, Padowitz said the justice system has since improved on how similar trials are handled.

“I really think that if there’s anything to be said about this case, it’s that it did have an impact nationwide, it did have an impact on legislation,” the former prosecutor said. “It made people really examine and think about what are we doing in this system. And provide alternatives that are appropriate age-based punishments and rehabilitation.”

By Samuel Howard

Sun Sentinel

September 30th, 2016

It’s been 15 years since Broward County’s Lionel Tate became in 2001 the youngest American sentenced to life in prison.

That sentence, and the case’s circumstances, aren’t any easier to accept for those closest to the case, despite the time that’s passed.

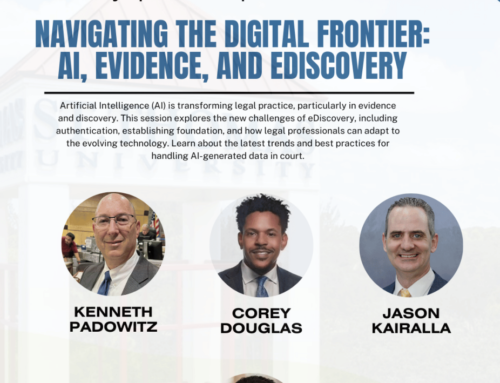

Seven of those participants — including the judge and lawyers who were part of Tate’s trial in 2001 — formed a panel Friday morning at the Broward County Crime Commission’s conference on juvenile and adolescent violence. They met to discuss and reflect upon the landmark case of the local boy convicted of first-degree murder in the death of a 6-year-old playmate.

Jim Lewis, Tate’s attorney during the murder trial, said a chief regret is personal: He became too close to the boy. Lewis said he took Tate bowling and introduced him to his own kids.

“If I made any mistake in the case, I became too close to him and probably because he really didn’t have a father in his life, was more of a father than a lawyer,” Lewis said. “I didn’t want him to go to prison for three years, either.”

The boy’s legal defense team notably declined a plea deal offer from then-prosecutor Ken Padowitz that would’ve sentenced him to three years in a juvenile center, one year of house arrest and 10 years of probation on a reduced second-degree charge.

But Tate, who was charged with killing Tiffany Eunick in 1999 when Tate was 12 years old, had a case fraught with complications from the start, Lewis and others agreed.

The justice system wasn’t prepared to handle a brutally violent case involving such a young defendant, they said.

Padowitz said he thinks those circumstances tied his hands. Wanting to be a “minister of justice,” Padowitz said, he instead had to be prosecutorial.

He was stuck “between a rock and a hard place,” faced with pursuing standard sentences either in the juvenile or adult systems that Padowitz considered unjust.Padowitz said he left it up to a grand jury, which charged Tate as an adult for first-degree murder. “I tried to do the right thing,” he said.

Senior Broward County Judge Joel Lazarus, who presided over the case, said he regrets “to this day” he didn’t appoint an attorney to work directly with Tate and oversee a psychological evaluation until after the appeals court ruling.

“The issue of competency … seemed to take a back-burner,” Lazarus said.

After an appeals court threw out Tate’s lifetime prison sentence in 2003, the teen violated the terms of his probation by taking part in an armed robbery of a pizza-delivery man and is now serving a 30-year prison sentence.

Tate, currently held at Everglades Correctional Institution in Miami-Dade County, is scheduled to be released from prison on Sept. 16, 2030, state records show.

Tate’s time in prison led to a “deeper dive” toward more run-ins with law enforcement, said David Watkins, director of equity and academic attainment at Broward CountyPublic Schools. Watkins oversaw Tate’s education after sentencing.

“I knew he was gone,” Watkins said after the panel. “He was institutionalized at this point.”

Although the case had its complications, Padowitz said the justice system has since improved on how similar trials are handled.

“I really think that if there’s anything to be said about this case, it’s that it did have an impact nationwide, it did have an impact on legislation,” the former prosecutor said. “It made people really examine and think about what are we doing in this system. And provide alternatives that are appropriate age-based punishments and rehabilitation.”