(Originally Published March 18, 2001 – Miami Herald)

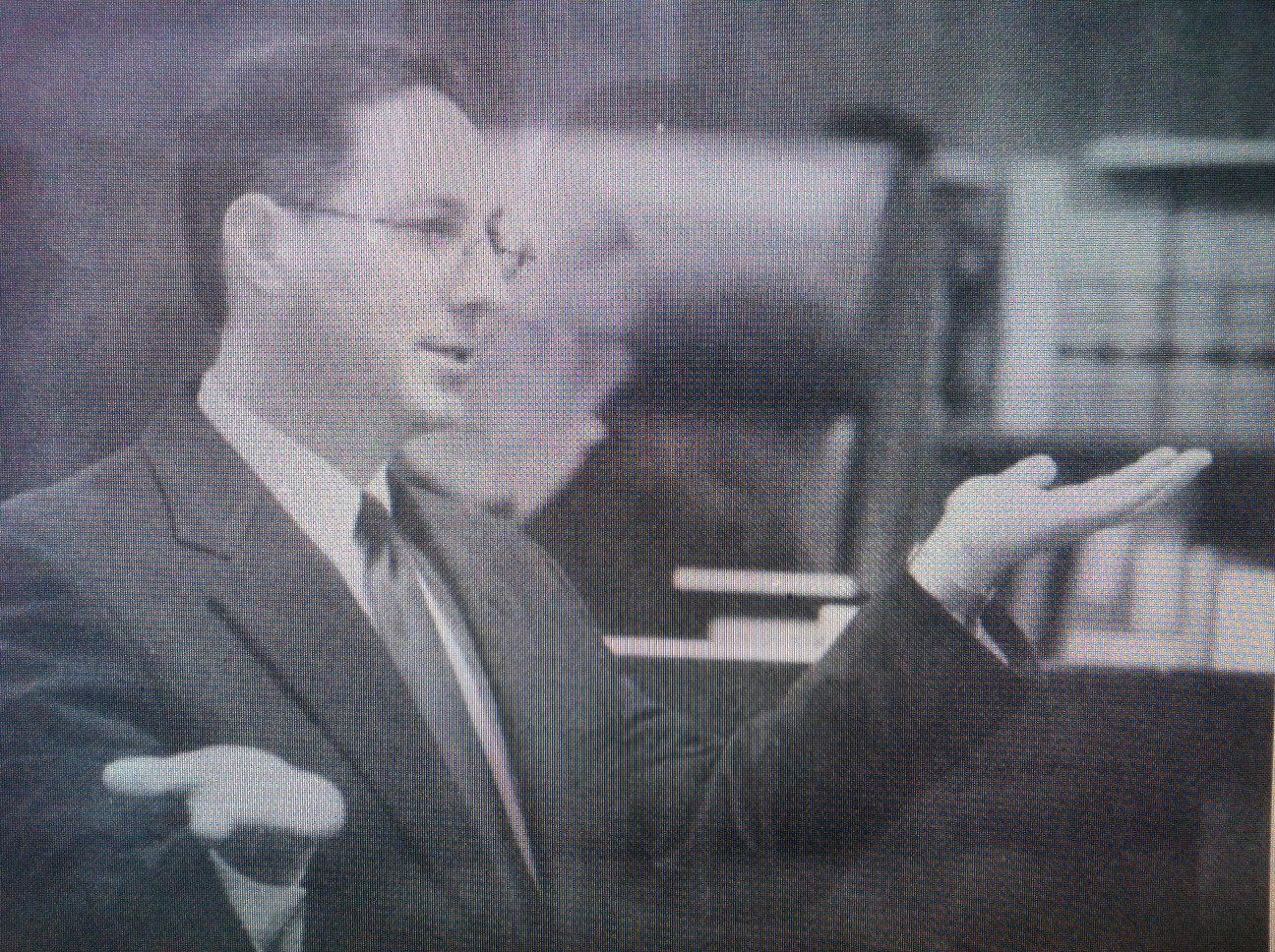

“Prosecutors don’t just seek convictions,” he says, leaning across his desk in a cramped office strewn with boxes of depositions and bundles of autopsy photographs. “They’re charged with a higher moral duty to ensure that justice is done.”

By CAROLINE J. KEOUGH

Miami Herald

March 18, 2001

Ken Padowitz is a true believer.

The man who fought to put Lionel Tate in prison for the rest of his life, then asked Gov. Jeb Bush to consider reducing the boy’s sentence, believes in justice.

He talks about it with the zeal old-time preachers reserved for fire and brimstone.

“Prosecutors don’t just seek convictions,” he says, leaning across his desk in a cramped office strewn with boxes of depositions and bundles of autopsy photographs. “They’re charged with a higher moral duty to ensure that justice is done.”

He knows it sounds corny. He knows there are those, including the judge in the case, who believe his vision of justice is skewed. He knows many of his colleagues don’t agree with what he has done. And he knows they snicker at his blustery performances in television interviews, touting himself as a “minister of justice.”

But he believes.

_________________________________________________

“He’s like an inventor. Ninety-nine percent of inventors invent so they can get a patent and make a bunch of money and be rich. But one in a hundred of them create so they can make the world a better place, and the money is a byproduct,” says defense attorney and former Assistant Public Defender Randy Haas, who met Padowitz the day they started law school at Nova Southeastern University together. “Ken is that one person. The convictions are a byproduct for him. He really wants to make the world a better place.”

__________________________________________________________________

“He’s like an inventor. Ninety-nine percent of inventors invent so they can get a patent and make a bunch of money and be rich. But one in a hundred of them create so they can make the world a better place, and the money is a byproduct,” says defense attorney and former Assistant Public Defender Randy Haas, who met Padowitz the day they started law school at Nova Southeastern University together. “Ken is that one person. The convictions are a byproduct for him. He really wants to make the world a better place.”

But he wants to help run it, too. His statistics tell the story:

At 40, he is a 15-year veteran of the Broward State Attorney’s Office with a 34-1 record in murder cases. He was the first prosecutor in the United States to introduce computer-generated reenactments into court. He has applied to be appointed as a judge four times.

His position in the Tate case may be unprecedented: He fought to convict the Pembroke Park boy while saying he’d seek clemency if he won.

The judge accused him of turning the justice system into a “game.” Talk show hosts accused him of being savagely cruel to Tate, who was 12 at the time of the crime. Hysterical letter writers accused him of casting aside 6-year-old murder victim Tiffany Eunick.

Padowitz says his own children, two boys, 8 and 12, figured deeply into his unusual stance.

In sentencing Tate, Judge Joel T. Lazarus said Padowitz’s actions “not only cast [him] in a light totally inconsistent with his role in the criminal justice system, but it makes the whole court process seem like a game, where if the results are unfavorable, they’ll run to a higher source to seek a different result.”

Padowitz says Lazarus’ words do nothing to deflate his pride in how he handled the case.

“I will wear that critique like a badge of honor,” Padowitz says. “Judge Lazarus said it’s not my role as a prosecutor to indicate that I would go to the governor because I didn’t feel the mandatory life sentence was appropriate. I think it is my role.”

As a politically ambitious college student, Padowitz interned for local politicians, occasionally assigned to sort their mail. Since the verdict in the Tate case, he’s needed someone to sort through his.

“Now that the trial was won, who should be prosecuted for the mental murder of Lionel Tate?” wrote a woman who saw Tate as the victim of a malicious prosecution. “Do not let him be a victim of the courts and your office.”

Another, outraged that Padowitz would seek clemency for Tate, wrote: “Would you feel the boy needs a break if your child was his victim!?! Do you have any concern for the lives ruined as a result of this murder? Does life have any sanctity for you!?!”

People who don’t understand his actions didn’t hear the evidence in the case, Padowitz says.

“Half the people in the world seem to be upset that I am asking the governor to hold a clemency hearing,” says Padowitz, who has accepted nearly every invitation from talk shows and newscasts. “The rest of the world seems to be upset that he’s not home with his mother right now. So the way I look at it, I must be doing the right thing.”

Here’s his logic:

When the case was assigned to him in July 1999, Tiffany’s injuries horrified him. Her liver was split, her skull fractured, her rib broken and her body bruised. In the juvenile justice system, Tate likely would have served six to nine months. That wasn’t enough, Padowitz thought. A grand jury agreed, and returned an indictment for first-degree murder. Padowitz offered Tate a generous plea deal of three years in a juvenile facility followed by 10 years probation and counseling.

Tate’s mother rejected it, saying the death was an accident and her boy shouldn’t spend a day in jail. Padowitz prepared for trial, privately telling friends and colleagues he’d be the first person on the plane to Tallahassee to ask for clemency if Tate got life.

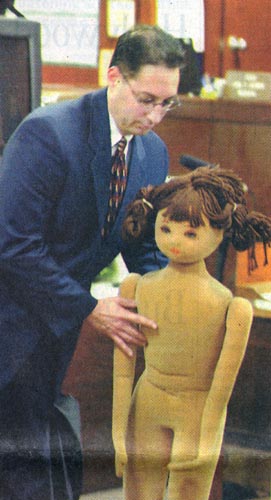

Meanwhile, he churned out legal arguments designed to squash the defense, who said the boy was only imitating his favorite professional wrestlers and didn’t mean to hurt Tiffany. Padowitz won nearly every motion.

His critics, including Judge Lazarus, say he should have reduced the charges if he didn’t think a life sentence was appropriate. Padowitz says he couldn’t toss out the grand jury’s decision. Defense attorneys complain prosecutors lead grand juries to return the indictments they want. Prosecutors, including Padowitz, say they don’t. The proceedings are secret, so neither side can be sure.

At trial, Padowitz pounded the jury with grisly autopsy photos and testimony from medical experts.

After Tate had been hauled away in handcuffs, Padowitz told reporters there were no winners in the case.

“Ken is in a tough position because he’s a zealous prosecutor who also has human kindness,” says Chuck Morton, head prosecutor in the homicide unit. “He’s pulled both ways as a human being. He’s got kids this age and he can identify with Tiffany’s family, but also with Tate’s fate.”

As Padowitz played lion tamer in the media circus, Morton teasingly printed out a new business card. “Professor Ken Padowitz,” it reads. “Minister of Justice.”

Padowitz keeps the card in his wallet, laughing as he pulls it out to show visitors.

But in his heart, he believes it’s true.