“The defense team was led by Ken Padowitz, a veteran trial attorney with a long history of embracing emerging technology for use in court. He’s no stranger to innovation—having previously introduced one of the first forensic animations ever admitted in Florida courts in the early 1990s. Now, over 30 years later, he’s pioneering again—this time with immersive evidence.”

Melissa Heidrick – Mar 01, 2025

ABA – Law Practice Division

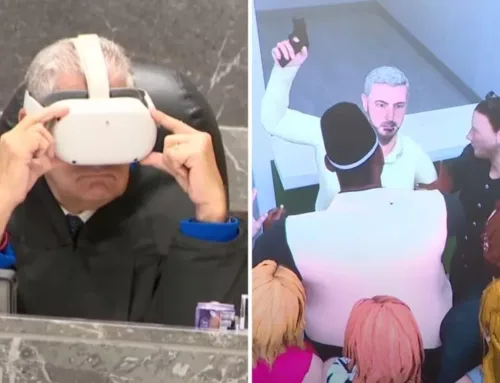

Is the future arriving ahead of schedule? In December 2024, a Florida defense team presented their expert’s opinion using virtual reality (VR). During a stand-your-ground hearing, Broward County Judge Andrew Siegel donned a Meta Quest 2 headset, stepping into the defendant’s perspective. This marks what is believed to be the first documented use of VR in a U.S. courtroom. Developed through forensic analysis, the VR visualization served as a demonstrative—not direct evidence, but a tool to illustrate and contextualize the defense’s argument.

The defense team was led by Ken Padowitz, a veteran trial attorney with a long history of embracing emerging technology for use in court. He’s no stranger to innovation—having previously introduced one of the first forensic animations ever admitted in Florida courts in the early 1990s. Now, over 30 years later, he’s pioneering again—this time with immersive evidence.

Why should legal professionals pay attention? Because VR and extended reality (XR) technologies aren’t just for gaming anymore—they’re making their way into legal practice. As hardware improves and we become more open to new tools, VR may become an important addition to our legal technology toolkits.

Unlike two-dimensional animations, VR can place the viewer inside the scene, allowing them to experience events from a specific perspective. Imagine the possibilities, not just for self-defense cases, but for accident reconstructions, complex fact patterns, any situation in which context and spatial relationships matter.

Padowitz recognized this potential early on––he kindly met with me in January of this year to discuss his experience, and explained, “One of the biggest challenges trial lawyers face is keeping the fact finder engaged. We assume that judges and juries listen intently for hours, but that’s just not how human attention works. Using demonstratives like VR can ensure that key evidence is not only seen but also understood.”

Studies have shown that VR experiences enhance memory retention, increase engagement and even evoke empathy and connection—crucial factors in persuasion. In this Florida case, the VR experience helped provide context that video footage didn’t—allowing the judge to see the defendant’s perspective leading up to the altercation.

Padowitz and his team approached VR with the same standards used for forensic animations—carefully aligning it with expert opinions and factual data. So, is VR in the courtroom a novelty, or the start of a larger trend? Watching the implications evolve may be the adventure of a lifetime.

Criminal Defense Trial Attorney Ken Padowitz

Criminal Defense Trial Lawyer and Law Partner Joshua Padowitz

played a vital role in the strategy for VR admissibility

Why?

Forensic animations have long been a powerful tool in litigation, but VR offers something different—immersion. Rather than watching a video play out from a fixed angle, the fact finder can step into the scene and experience it. This shift from passive viewing to active engagement has profound implications for memory, retention and decision making.

Studies on VR and cognitive processing indicate that VR experiences are encoded more like real memories than traditional media. This means that instead of simply recalling a video or demonstrative, fact finders may remember the experience as if they had been there themselves. In a trial setting, this has the potential to deepen engagement and improve comprehension.

Padowitz saw this firsthand when presenting VR to the judge. “One of the biggest problems trial lawyers face is making sure that critical evidence isn’t just shown, but truly understood,” he said. “Virtual reality lets us do that in a way that has never been possible before.”

VR can also evoke strong empathy—something that traditional exhibits may struggle to achieve. In cases where perspective matters, such as self-defense claims or accident reconstructions, placing the fact finder inside the moment can bridge the gap between abstract testimony and lived experience.

VR experiences can activate emotional and cognitive empathy in ways that 2D animations may not, which makes them particularly attractive for matters where it’s essential to understand what a party saw, heard and perceived. Padowitz specifically leveraged this aspect in his defense strategy. By placing the judge in the defendant’s position, the VR experience provided a critical piece of context—one that might have been difficult to convey through words alone. “This wasn’t about dramatization,” he noted. “It was about making sure the judge fully grasped what my client saw and why he reacted the way he did.”

How?

Padowitz’s team approached the process of developing a VR demonstrative with care—starting with on-site forensic data collection. “We brought in an expert team from California,” Padowitz recounted. “They took precise measurements, analyzed the scene and gathered hundreds of photographs to ensure accuracy. From there, we reconstructed the event in a digital space based on forensic data.”

Once the forensic team established the foundational evidence, the next step was transforming raw data into a virtual reconstruction. This process involved:

- Accident reconstruction and expert opinion integration. The VR experience was built upon expert analysis, ensuring it aligned with forensic findings and testimony.

- 3D modeling and scene recreation. Animation experts used real-world measurements and photographic evidence to create a digital replica of the location.

- Animation and perspective calibration. To maintain fairness and accuracy, the animation was designed to reflect what the defendant saw in real time.

- VR deployment and courtroom readiness. Once the VR experience was finalized, the legal team tested it on multiple headsets and prepared it for courtroom presentation.

The headset used in this case—the Meta Quest 2—is a stand-alone headset capable of rendering immersive 3D environments without requiring an external computer. VR allows the fact finder to actively look around, control their perspective and experience the environment in a way that mirrors reality. In practical terms, this means that in a self-defense case like Padowitz’s, a judge or jury isn’t just watching an animation—they are stepping into the defendant’s shoes.

How Hard?

Admissibility

It’s important to remember that for Padowitz’s matter, the VR experience was not introduced as substantive evidence, but as a demonstrative exhibit––and these must clear judicial scrutiny. Generally, admissible evidence falls into two categories:

- Substantive evidence. This includes testimony, documents and physical evidence that directly proves or disproves a fact in the case. Governed by Federal Rule of Evidence 401, substantive evidence must make a fact of consequence more or less probable to be admissible.

- Demonstrative evidence. Unlike substantive evidence, demonstrative exhibits explain or illustrate the substantive evidence previously admitted. The Fifth Circuit has described demonstrative evidence as “evidence admitted solely to help the witness explain his or her testimony,” cautioning that such evidence “has no probative force beyond that which is lent to it by the credibility of the witness whose testimony it is used to explain.”

For a demonstrative to be admissible, it must relate to admissible substantive evidence or testimony, it must fairly and accurately represent that evidence and it must help the fact finder understand or evaluate the case. And even when demonstratives meet these criteria, they can still be excluded under Federal Rule of Evidence 403 if unnecessarily cumulative, unfairly prejudicial or misleading.

Because demonstratives must be authenticated as a fair and accurate representation of other admissible evidence, testifying experts need to be involved in the development process. If the expert whose opinion the VR represents can vouch for its accuracy under oath, it becomes harder to challenge.

When introducing VR demonstratives, attorneys can anticipate objections—particularly regarding accuracy and fairness. Key questions will arise: Does the demonstrative accurately reflect the facts, or could it be seen as biased or speculative? Could the immersive nature of VR unduly influence the fact finder’s emotions? Is the VR demonstrative properly tied to admissible evidence and expert testimony?

Buy-In

Even when a demonstrative is admissible, convincing many judges to don a headset could prove challenging. Judicial hesitation toward new technology is common. However, in Padowitz’s case, Judge Siegel was receptive—an openness that proved crucial in allowing the defense to present the visualization.

Padowitz’s team also endeavored to make the user experience smooth. They pre-tested and set up multiple headsets, to allow all parties to access the same perspective, and avoided speculative or potentially misleading or dramatic elements in the experience. Their approach highlights a key takeaway for attorneys: when introducing emerging technology, precision and preparation can mean the difference between a powerful demonstrative and one that never makes it in front of the fact finder.

Looking to the Future

Just a year ago, VR in the courtroom might have seemed futuristic. But with technology advancing at breakneck speed, what once felt like science fiction is quickly becoming reality. Hardware that once felt bulky and impractical is getting lighter, resolution is improving and more intuitive interfaces make immersive experiences easier to use.

With billions flowing into XR from tech giants like Meta, Apple and Google, both hardware and software are evolving at an unprecedented pace. Meta’s announcement of Orion smart glasses and Google’s unveiling of Android XR signal a shift toward both adoption and smaller, more comfortable form factors—paving the way for smart glasses with integrated displays. What once seemed like a niche technology for gaming is now on the path to mainstream adoption across industries, including medicine, engineering, education and yes—even litigation. With this rapid evolution, the legal field may adopt immersive technology sooner than we expect.

To stay ahead, legal professionals should track how immersive tech is shaping other industries—especially those of their clients. We can stay informed on evidentiary standards––as XR demonstratives become more common. We can anticipate opposing counsel’s use of VR, and we can experiment with immersive tools now in low-risk scenarios––learning how technology works may give you a critical edge. Judges, litigators and e-discovery professionals who stay ahead of emerging trends will have a distinct advantage—not just in using these tools, but in understanding how to challenge or defend them in court.

Let’s stay engaged, informed and curious––the future is arriving fast, and those who prepare now are poised to lead the next era of legal practice.